The Beginning of Karate

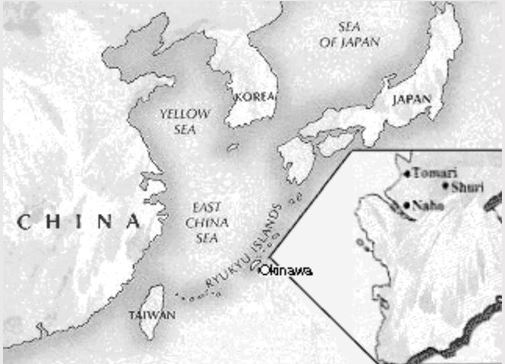

Karate in Okinawa was first taught as “ti” and was not changed until just before WWII when the word “te” was attached to all styles of self-defense and martial arts. The “ti” styles were taught in secret. In this article, we will talk about one of the original “ti” arts, Tomari-ti. Variaous of ti was also taught in the villages of Naha and Shuri, but Tomari-ti was an art that stood by itself.

Tomari was a small fishing village, the main port for all seafaring traffic in Okinawa. Because of the coral reefs around the islands, this was the safest, and only, port for ships to dock. Over the many centuries, the port at Tomari brought in people from all over the world. When seafaring was the major transportation between Okinawa and China, Chinese emissaries would pass through.

The Shaolin temples were often at risk by the Chinese government and invaders – depending on the emperor and which country wanted a piece of China, and Okinawa became refuge for many of these monks. The Shaolin monks were known for their prowess and fighting abilities and were a threat to those in power. If the emperor at the time didn’t support them, he burned the temples.

This set the scene for monks leaving China and going to places elsewhere. Many passed through the port of Tomari.

Ti is the original art of Okinawa. There was probably some Chinese and Micro Polynesian influence from the travelers that came to the islands, but the people of Okinawa developed their own effective style of defense. Early records trace the beginning of ti to around 600 A.D., but it is safe to assume even before then the Okinawans had their own combat style.

Over the years, the three styles, Naha-ti, Shuri-ti, and Tomari-ti continued to grow. In the 13th Century, a group of Chinese families relocated in Okinawa, at the invitation of the Okinawan King Sho-Hashi. Their expertise in kung fu began to meld with the three styles.

Ti becomes Te

It was during this time, with the Chinese influence, that “ti” became “te.”

Tomari-te is known for the brutal resolutions of conflict, and many instructors refused to teach this art.

Tomari-te is a guerilla style of combat. Mountains and jungles surrounded the area, and there are stories of monks living in the caves in the mountains where they held their training sessions. Because of the brutality of the art, it was taught in secret, especially after 1609 when the Japanese invaded Okinawa.

The Japanese trained to fight in open battle fields, like the Europeans, and were not trained to fight in the mountains. The Okinawans confounded them with their hit and run tactics, the same way our U.S. Special Forces now fight.

It should be noted at this time many great masters taught U.S. troops in this fighting style, including Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of modern Aikido. Ueshiba Sensei, the founder of the Art of Peace, had obtained a different black belt in fighting arts. He realized that at 70 years old, “at my age, getting hit hurts.”

Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of modern Aikido. Ueshiba Sensei, the founder of the Art of Peace, had obtained a different black belt in fighting arts. He realized that at 70 years old, “at my age, getting hit hurts.”

Aikido was not new; all arts teach the timing techniques to avoid attacks and use de-escalation theories to fight with. This is in no way to take away the fact that Ueshiba Sensei was a great master.

He was famous for being the first to demonstrate techniques that use the high ranks of the hidden systems which he had pledged to never reveal to the public. The old masters had the realization that the Salem-witch-hunts and the current ongoing cults would be more than happy to try to claim what they were capable of doing as a result of cultism – without understanding or realizing that the true high rank masters have been taught to protect or to free the innocent.

Always a Changing Art

I was fortunate to train with six true grandmasters from different systems that were close friends who trained together, traveled together, played together, and spent years together discussing theory and techniques to prove their theories. They often exchanged students so they could get a hands-on experience as to what worked against what style or technique. These men were smart enough to change and improve what they taught so they would not have baseless techniques for the sake of leaving it in because of tradition – teach because it has aways been taught.

Karate is based on survival. In order to do that, an instructor must be willing to adapt to change and add on to their training. That is why the Japanese include archery as a new extension of the art – like we of today must include firearms.

A realist will increase his weapons, a purist is more like a cult and will not change to improve his system while staying pure. The purist and his students have stopped progressing, are being passed up, and eventually become relics. Like the dinosaur, they will become extinct due to their inability to evolve with the times and the world around them.

Shotokan is a current example of this. Funakoshi’s heritage is directly related to the Tomari-ti system, along with others, and his main reason to form Shotokan was to teach high school students’ physical education and not combat skills. That was the sole point in having a universal ranking system in 1924, and made the tournaments designed not to damage opponents. Up to that point, the matchers were designed to see who was best, in which Funakoshi himself was a champion in these matches.

After training and obtaining six black belts in different fighting styles while at the same time training with Master Juri, Master Juri and Master Nakiyama had requested that I train and teach under Okinawa’s banner. At the time, Kung Fu was being made a fool of because TV shows like Kung Fu.

They thought Bruce Lee would eventually bring a bad name to the art due to his mob and Hollywood connections – which later came to be the case. After these Hollywood shows, the reputation of the art began to spiral downward, and the art became a joke based on impossible techniques; flying over walls, voodoo-like spells, fighting twenty armed men, and drugs were constantly a sideline. The modern arts became about mysticism, the supernatural, Superman in a gi, and big money.

The Goal is to Protect our Own

In twenty years, our code of morality and ethics was no longer in the forefront for which the art was originally taught – to protect.

Today karate is big money, both for instructors and promotors. There is little honor or discipline in the ring. Judges play politics. If you have superior techniques, an ass-kissing referee that needs a favor would willingly avoid giving an opponent a point. Until the opponent realizes the only way to prove his technique is by taking out the other opponent with a technique that damages the other fighter to make it clear his techniques are superior.

It is for these reasons that straight-forward traditional styles cannot be taught commercially. It is up to the instructor to pick out qualified students, not his banker. The students are responsible for meeting some of the needs of the instructor. A good instructor works on karate 24 hours a day. Ti or Te, you really don’t have time to choose which one broke your elbow.

I have read about other instructors that still do Ti and they are amazed that the same katas are used. But the bunkai that the instructors teach are easy to see and basically self-explanatory without even knowing the hidden bunkai in them.

All katas that are completely known by an instructor would include throwing, grappling, target attacks (five techniques of bone separation, muscle separation, sealing the breath, sealing the vein, and cavity press), locks and stop-hit moves.

Without knowing those elements, you cannot possibly know a kata. Anyone claiming to be a master should be able to see these things in any kata from any style unless the kata was invented by a fool just trying to make a knife dance and not a kata.

This article was written by Master Pickett sometime in the 1990’s.

I found it among his papers and am sharing it with you.

(This is his original work with only slight editing)

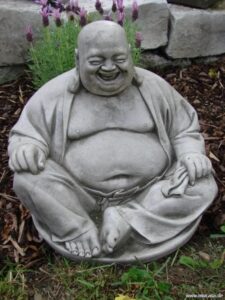

This was a Buddhism where the monks believed in obtaining nirvana through meditation and chanting, and entering the monastery meant forgoing all prior knowledge of their family’s fighting art. Violence was forbidden in the temple.

This was a Buddhism where the monks believed in obtaining nirvana through meditation and chanting, and entering the monastery meant forgoing all prior knowledge of their family’s fighting art. Violence was forbidden in the temple.